- Home

- Elizabeth Catte

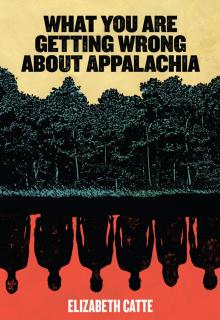

What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia

What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia Read online

Copyright © 2018 Elizabeth Catte

All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

First edition 2018

ISBN: 978-0-9989041-4-6

Belt Publishing

1667 E. 40th Street #1G1

Cleveland, Ohio 44120

www.beltpublishing.com

Book design by Meredith Pangrace

Cover by David Wilson

INTRODUCTION

PART I

Appalachia and the Making of Trump Country

PART II

Hillbilly Elegy and the Racial Baggage of J.D. Vance’s “Greater Appalachia”

PART III

Land, Justice, People

SUGGESTED RESOURCES

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

INTRODUCTION

Six months before the 2016 presidential election, my partner and I moved from Tennessee to Texas, to a modest-size city best known for housing the largest oil refinery in the United States. It also has the distinction of having some of the highest rates of brain cancer, leukemia, stomach cancer, nervous system and skin disorders, and respiratory ailments in the country.

To convince ourselves that the move hadn’t been a mistake, we talked often of our lives in Appalachia, where we lived in the shadow of paper mills, mines, and coal-burning plants. These discussions later became the justification for our sudden departure. We expected culture shock and homesickness in Texas, but we did not anticipate a baptism by sulfur dioxide, hexane, and pentane. If two people raised on heavy metals and slurry call time, it’s fair to say that things might be fucked. By the time you read this, we’ll be back home.

We longed for home for less clinical reasons as well. In Texas, upon hearing where we were from, everyone wanted to talk to us about a new book called Hillbilly Elegy, by a guy named J.D. Vance. The best-selling “memoir of a family and of a culture in crisis,” now set to be turned into a film by Ron Howard, had become our political moment’s favorite text for understanding the lives of disaffected Trump voters and had set “hillbillies” apart as a unique specimen of white woe. Using the template of his harrowing childhood, Vance remakes Appalachia in his own image as a place of alarming social decline, smoldering and misplaced resentment, and poor life choices. For Vance, Appalachia’s only salvation is complete moral re-alignment coupled with the recognition that we should prioritize the economic investments of our social betters once more within the region.

It’s a strange experience to be grilled about the social decline of “your people” less than five hundred yards from a refinery that gives poor African Americans cancer, but that is what happened to us. At the local university, people whose wall art had been eaten by pollution were suddenly and deeply fascinated by the tragedies of Appalachia.

“Why don’t more people just leave?” they asked, while we silently calculated how much money we’d lose by moving back home. If we were destined to be poisoned by corporations and deprived of civil liberties by corrupt politicians, better the devil we knew, we reasoned.

Election season cast Appalachia as a uniquely tragic and toxic region. The press attempted to analyze what it presented as the extraordinary and singular pathologies of Appalachians, scolding audiences to get out of their bubbles and embrace empathy with the “forgotten America” before its residents elected Donald Trump. After the election, when it became too late, the pendulum swung in the opposite direction and empathy became heretical. Appalachia, political commenters proclaimed, could reap what it had sown.

There’s not a single social problem in Appalachia, however, that can’t be found elsewhere in our country. If you’re looking for racism, religious fundamentalism, homophobia, addiction, unchecked capitalism, poverty, misogyny, and environmental destruction, we can deliver in spades. What a world it would be if Appalachians could contain that hate and ruin for the rest of the nation. But we can’t.

In the region, we often speak of Appalachia as a mirror that reflects something troubling but recognizable back to the nation. Some cultures avoid mirrors in periods of mourning, afraid that the void created by grief might become a portal that causes something sinister to leak out. These days, an image like this seems fraught with extra meaning.

My partner and I went about our daily lives in Texas trying to convince people that the oil industry and the coal industry weren’t fundamentally different to the person with undrinkable water. Cataloguing contemporary essays and interviews about the “Appalachia problem” became something of a hobby for me. I quickly discovered that the most telling aspect of these essays and interviews wasn’t what they said about Appalachia, but what they didn’t say.

According to the bulk of coverage about the region in the wake of Trump’s election and the success of Hillbilly Elegy, currently at fifty weeks on the New York Times Best Seller list, I do not exist. My partner does not exist. Our families do not exist. Other individuals who do not exist include all nonwhite people, anyone with progressive politics, those who care about the environment, LGBTQ individuals, young folks, and a host of others who resemble the type of people you’ll meet in this volume. The intentional omission of these voices fits a long tradition of casting Appalachia as a monolithic “other America.”

While many regional groups experience this treatment, as scholar Elizabeth Engelhardt recently wrote in the journal Southern Cultures, “Appalachia stands out, however, in the sheer length of time that people have believed it could be explained simply, pithily, and concisely…again and again Appalachia is relegated to the past tense: ‘out of time’ and out of step with any contemporary present, much less a progressive future.”

With this in mind, What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia has two objectives: to provide critical commentary about who benefits from the omission of these voices, using Appalachian history to push back against monolithic representations of the region, and to openly celebrate the lives, actions, and legacies of those ignored in popular commentary about Appalachia. The critic bell hooks wrote, “With critical awareness, we must recognize the spaces of openness and solidarity forged in the concrete experience of living in communities that were always present in radical spaces in Appalachia both then and now…I believe it is essential for unity and diversity to gather those seeds of progressive change and struggle that have long characterized the lives of some individuals.”

I am a historian and What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia is filled with history, but it is not a comprehensive primer. Rather, it approaches history as the seeds that hooks describes, and hopes to plant in your mind something that might blossom if you examine the region more closely. This isn’t, however, another one of those “voice for the voiceless” projects. For those who already know and celebrate a different Appalachia—and they are many—this is solidarity.

WHAT IS APPALACHIA?

Appalachia is, often simultaneously, a political construction, a vast geographic region, and a spot that occupies an unparalleled place in our cultural imagination. We’ll start with the most basic information to get our bearings straight. Appalachia is an approximately 700,000-square-mile region of the eastern United States. It is loosely defined by the arc of the Appalachian Mountains that begins in Alabama and ends in New York, although the mountains continue into Canada.

There are thirteen states with Appalachian counties—Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, Kentucky, West Virginia, Ohio, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New York—and West Virginia is the only state entirely with

in Appalachia. Appalachia’s population is approximately twenty-five million individuals, although the rate of out-migration, especially among young adults, is high. You might think our biggest export is coal but it’s actually people.

Defining Appalachian culture is often a top-down process, in which individuals with power or capital tell us who or what we are. These definitions tend to reduce people to pathologies, but can also include more clinical assessments, such as those that followed the creation of the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) in 1965. The ARC defined Appalachia as a coherent political entity during the Johnson administration’s War on Poverty. It still exists (if precariously, at the moment) to monitor and create economic development within the region.

Although it made use of the existing geographical and cultural boundaries of the region, the ARC’s primary lens was economic. One of its first tasks was to grade each county thought to be Appalachian on a scale of economic distress in order to administer federal aid efficiently. By its design, the region came to be defined by poverty, and subsequently poverty came to be defined by the region. This logic, like the War on Poverty itself, left an indelible imprint. You’ll see what I mean soon.

The ARC’s definition of Appalachia includes 420 counties, and therefore provides us with the most official scope of the region. There are, however, places like the Shenandoah Valley that are part of historic but not modern Appalachia. The reason? The area’s political leaders simply didn’t want to be part of the ARC’s Appalachia and therefore severed themselves from the regional identity. Appalachia is nothing if not messily defined.

It is important to understand that whatever “Appalachian” is, it should first be seen as a flexible regional identity that has nothing to do with ethnicity. More than 80 percent of Appalachia’s population identifies as white, but for the past thirty years, African American and Hispanic individuals have fueled more than half of Appalachia’s population growth. Nonwhite Appalachians, as a group, tend to be younger and less likely to depopulate the region than their white counterparts. I’m hesitant to tell you who Appalachia is, but I can tell you who helps keep it alive: young individuals who work in racially diverse fields, including education, hospitality, and healthcare.

By several metrics, many parts of Appalachia are not places of robust racial and ethnic diversity, but the region is more diverse than it’s presented in books, essays, and photographic projects. Only two Appalachian states—Kentucky and West Virginia—were identified among the ten “whitest” parts of the United States, behind Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Iowa, Idaho, and Wyoming.

Many Appalachians are working-class but their realities complicate definitions of the white working class that are incredibly popular at the moment. Coal miners, centered in political rhetoric as the face of the forgotten white working class, earn an average salary of $60,000 to $90,000 a year. It is more accurate to describe coal mining as a blue-collar profession that commands a middle-class salary, a rarity in our present moment and certainly an employment sector that is shrinking beyond hope. There are currently around 36,000 miners in the entire region. The real forgotten working-class citizens of Appalachia, much like the rest of the nation, are home health workers and Dollar General employees. They’re more likely to be women, and their exemption from the stability offered by middle-class employment is not a recent phenomenon.

This volume will offer many thoughts about why we love these imaginary Appalachias, but it’s important to first understand that the impulse to create them is old. One of my favorite historical documents is an editorial printed by a leftist newspaper serving southwestern Virginia coal country in the 1920s. The editorial mocked the national perception that Appalachia was home to a homogenous group of white people awaiting the attention and salvation of experts. Editor Bruce Crawford eviscerated a reporter who had traveled to the region to find “the mountain white,” a “distinct race measuring up to all specifications” desired by “wild-eye reformers.”

“In this little city buried away among the wretched ten thousand people over whom good-hearted philanthropists are currently weeping there was discovered a mountain white principal of a Norfolk high school and a high school teacher from Richmond,” Crawford wrote, “and thereupon our traveler fled. He was last seen heading for the Kentucky mountains where we hope he will find people just as white and just as mountainous.”

If you substitute “philanthropist” with “venture capitalist,” you’ll find that this reality has not shifted much for some.

Using Appalachians to fill made-to-order constituencies, anchored by race, is a tired game. Social upheaval, from the Civil War to the civil rights movement, often triggered, and still does, a larger fascination with Appalachia. These projections do a disservice to both Appalachians and other economically and socially disadvantaged groups by pitting their concerns against one another instead of connecting them.

Discussions of Appalachia’s economy often trade on the perception that the region’s people are dependent on government assistance, what we in the region sometimes call transfer payments. Historian Jessica Wilkerson recently wrote, “Writers and their readers play into political arguments that simplify Appalachia as a region that absorbs large amounts of government aid but gives back little, making it easier to condemn the people who live there.”

Dependency narratives fuel popular talking points among individuals on both sides of the political aisle. They are often presented without acknowledgment that corporate welfare runs Appalachia. Corporate welfare allows business to shirk their tax burdens, hoard land, and wield enormous political influence while local communities suffer. Narratives of dependency conceal the uneven distribution of wealth that haunts Appalachia and indeed, much of the nation.

In 1979, Harvard University paid just $2.82 in annual property taxes on 11,182 acres of land in Martin County, Kentucky, an arrangement that received scrutiny after the ARC published an extensive study of land ownership in 1982. Appalachians are in the process of updating the land study, but what its original authors discovered in the 1980s is likely still true. Private businesses and out-of-state landowners do not carry anything close to an equitable local tax burden, making it impossible for communities to survive, let alone thrive.

Conservative political commenter Bill Kristol, for example, who often shames the poor via dependency narratives, earned his PhD from Harvard in 1979, during a time when impoverished Kentuckians subsidized his alma mater’s endowment. These are connections that are as worthy of study as lurid assessments of Appalachian welfare rolls, but they are largely uninteresting to those often speaking for or about the region.

Many Appalachians are poor, but their poverty has a deep and coherent history rooted in economic exploitation. The coal industry is no longer a significant employment sector in Appalachia, but the dominance of coal’s extractive logic has permanently ruined people and land in ways with which we must still contend. The people of Appalachia are predominately white, but the region is adding African American and Hispanic individuals at a rate faster than most of the nation. The average Appalachian is not, then, a white, hypermasculine coal miner facing the inevitable loss of economic strength and social status, but the average Appalachian’s worldview may be impacted by individuals with cultural capital who are constantly assuming we are all made in that image.

If I sound cagey about providing resolute and emphatic markers of “Appalachia-ness,” it is because people woefully overuse the term “Appalachian culture.” This is particularly true in our current moment that fetishizes the presumed homogeneity and cohesiveness of the region and uses these characteristics to explain complex political and social realities. Appalachian scholars and activists often prefer to stress our interconnectedness to other regions and peoples rather than set ourselves apart as exceptions. Individuals in Appalachia, for example, offered support and solidarity to communities in Flint and Standing Rock, understanding that the struggle for clean water is local, but also national and global.

> Many of the people you’ll meet in this volume self-identify as Appalachian. I will not ascribe a culture to them, cohesive or otherwise, but I will locate them in shared experiences such as the struggle to arrest environmental destruction, to secure workers’ rights, to demand clean water, and to preserve folkways. These struggles are ubiquitous in Appalachia but are not unique to the region. The individuals you’ll encounter include Florence Reece, who fought mine wars with songs. Ollie Combs, a widow who put her body in the path of machines is here, and so is the Highlander Folk School, where civil rights leaders trained in nonviolent resistance. You’ll get to know the people and projects of Appalshop and WMMT, media organizations focused on Appalachian issues, and individuals like Eula Hall, who tirelessly promoted rural health care.

Since Vance and his fans have made it acceptable to remake Appalachia in one’s own image, let me do the same and create a volume with an image made in my own. Far from being monolithic, helpless, and degraded, this image of Appalachia is radical and diverse. This image of Appalachia does not deflect the problems of the region but simply recognizes the voices and actions of those who have struggled against them, often sacrificing their health, comfort, and even their lives. It is an image projected by bodies against machines and bodies on picket lines and bodies that most assuredly are not always white. This image of Appalachia won’t be coming to a theater near you courtesy of Ron Howard, and we are all better for it.

PART I

APPALACHIA AND THE MAKING OF TRUMP COUNTRY

FROZEN IN TIME

On a frosty January morning in 2006, an explosion occurred in a coal mine owned by the International Coal Group in Sago, West Virginia. The explosion instantly killed one miner. Twelve others became trapped by debris, flames, and toxic gas. Their first shift after an extended New Year break had gone terribly wrong. All the missing men were fathers, some to young families, and the world watched as rescue crews tried to pinpoint their location in vain for two days.

What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia

What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia